🌍 Your 2026 prediction bets are in

We asked, you answered, and experts weighed in on 2026

DOE’s living climate tech commercialization reports with OTT’s Vanessa Chan

Historically, research and innovation have been the Department of Energy’s bread and butter, but with global temps creeping up and climate tech at a critical inflection, it’s all about “deploy, deploy, deploy.”

The DOE restructured last year to better collaborate with private industry, moving from research and development (R&D) toward demonstration and deployment (D&D). [Our Founder’s Guide to DOE provides a roadmap for startups engaging with the department’s programs and opportunities.]

When it comes to meeting the Biden administration's ambitious decarbonization goals, the name of the game is “public-private partnership.” And as the DOE spearheads the public sector effort, leaders across its many offices decided to get everyone on the same page. That is, the same 250+ pages.

After months of discussions with the private sector, the DOE unveiled their “Pathways to Commercial Liftoff” reports on Tuesday, spelling out the current state, challenges, and potential pathways to “liftoff” for climate technologies—starting with hydrogen, nuclear, and long duration energy storage.

As David Crane, director of the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations (OCED), puts it, this is a “first-of-a-kind informational approach” by DOE to accelerate commercialization of essential novel clean energy technologies.

“The clean energy industrial strategy will be private-sector led, government-enabled,” Jigar Shah, director of the Loan Programs Office, said. “These reports serve as a resource intended to inform decision making across industry, investors, and the broader stakeholder community and reflect the challenges and optimism of the private sector allocating capital to these sectors.”

The DOE’s Liftoff reports intend to serve as “living documents” tracking the demonstration and deployment of climate tech, based on continued engagement between the public and private sector.

We sat down with Vanessa Chan and Lucia Tian from the Office of Technology Transitions to break down the reports’ call to action: Here are the barriers. Now let’s unlock them.

With the trifecta of US climate legislation in place and record-breaking innovation and investment, the climate tech ecosystem is primed for commercial liftoff.

The three reports DOE shared this week cover long-duration energy storage, clean hydrogen, and advanced nuclear (with a breakdown on carbon management coming soon).

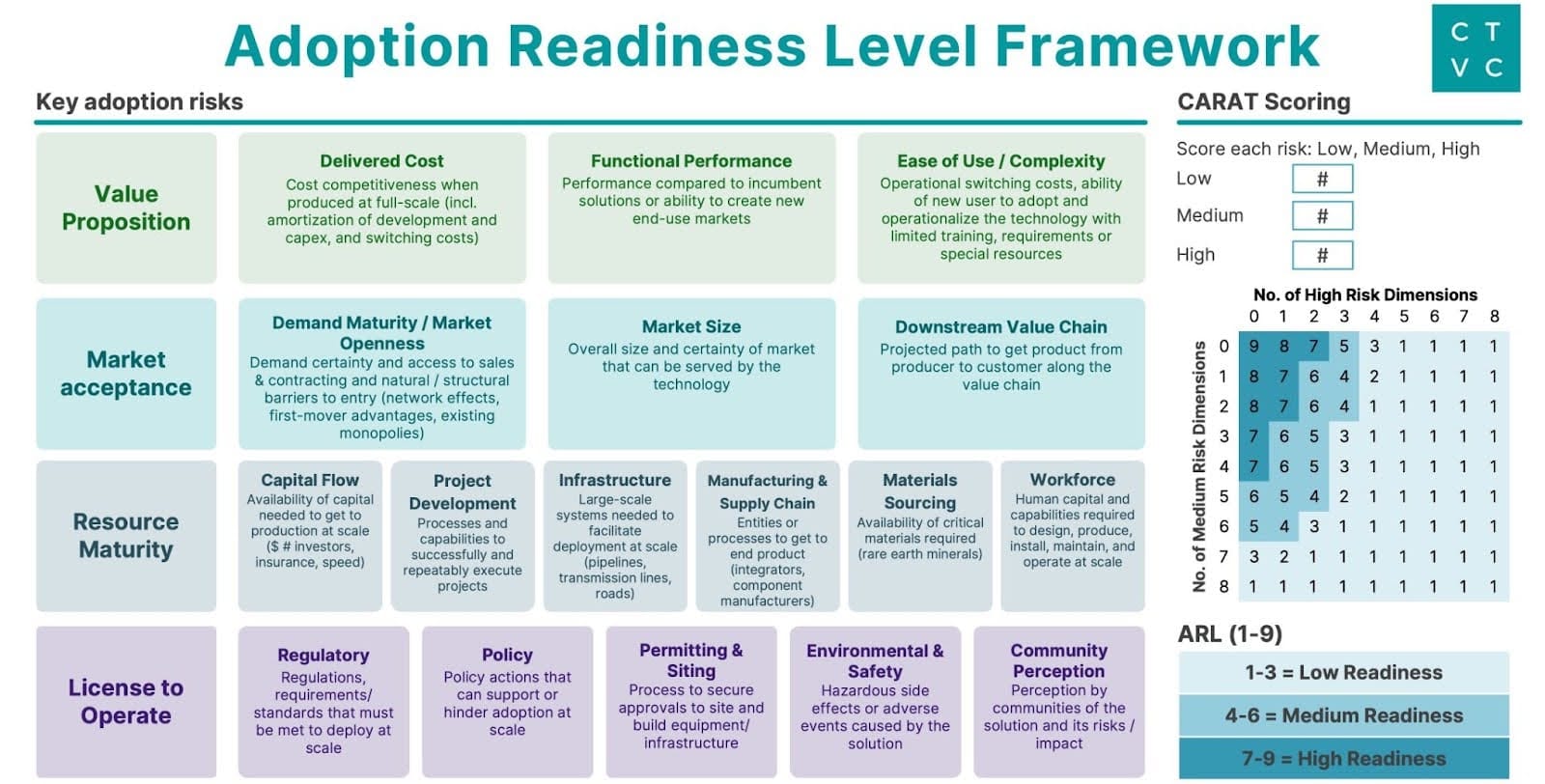

Founders, investors, and the DOE are all familiar with tech readiness levels (TRLs), but technology is just one dimension of risk on the pathway to commercial liftoff.

To set the new standard for commercial adoption, the DOE created adoption readiness levels (ARLs)—a checklist framework that considers factors like costs, supply chains, regulations, and market acceptance.

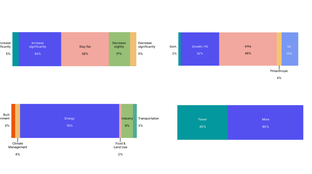

The ARL system breaks risks down into four categories:

Within these four areas are 17 subcategories, which are scored individually as low, medium, or high risk. By tallying up the number of medium and high risk dimensions and mapping those on a matrix, you get an ARL score of 1-9—reflecting not just the maturity of the tech like TRLs, but also the market conditions necessary for commercial adoption.

More consideration of industry, rather than innovation alone, is a shift in thinking at DOE that goes beyond just these reports. Offices across the department are incorporating ARLs into their processes and decision-making.

We spoke with Vanessa Chan, Chief Commercialization Officer and Director of the Office of Technology Transitions (OTT), about bringing her private sector experience to DOE and how she hopes companies and investors will use the ARL framework and the Liftoff reports.

We spoke with Vanessa Chan, Chief Commercialization Officer and Director of the Office of Technology Transitions (OTT), about bringing her private sector experience to DOE and how she hopes companies and investors will use the ARL framework and the Liftoff reports.

How did the idea for Liftoff reports originate and why did DOE decide to share them in this type of format?

Spending the last 20 years doing commercialization, one of the things I found is that we oftentimes are very much “technology push” [vs. market pull]. At McKinsey, where I co-led the innovation practice, we were working with large companies spending billions of dollars in R&D, asking the question, ‘what is preventing our technology from getting out the door?’ A lot of it had to do with things like with regulatory risks, the value proposition, the cost structure.

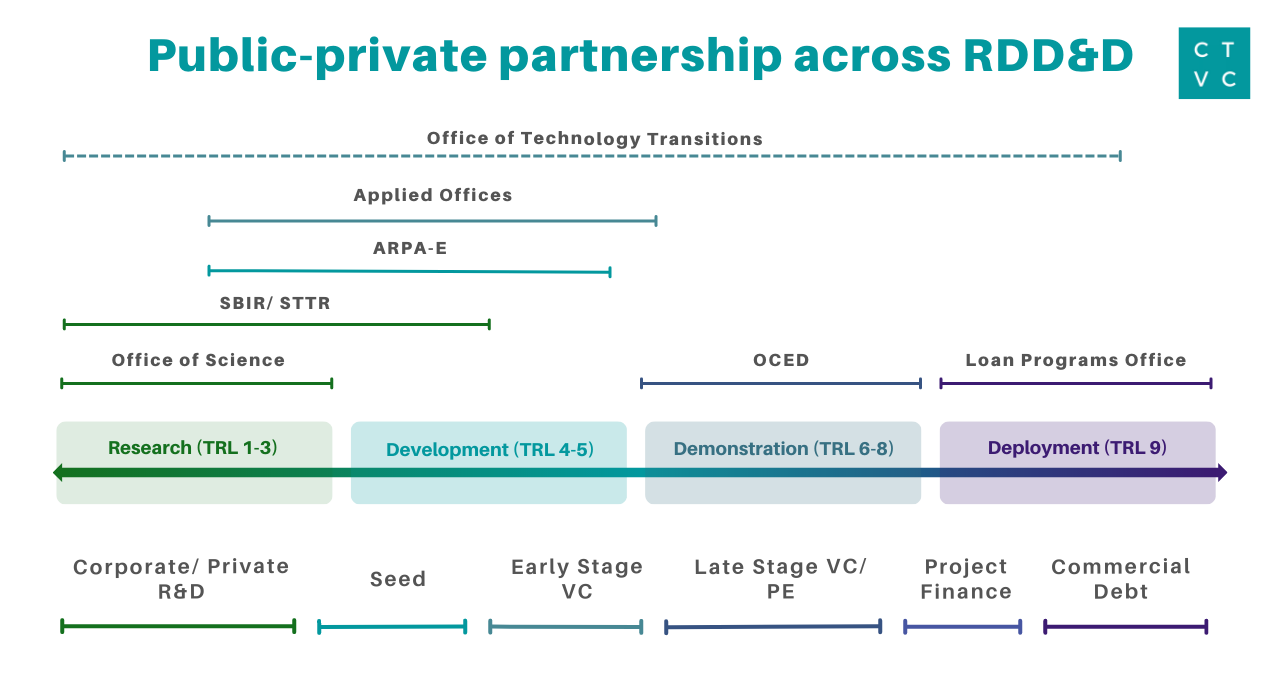

My job as Chief Commercialization Officer and the director of the Office of Technology Transitions (OTT) is to drive private sector uptake of clean energy technologies. If you think about the different risk profiles along the RDD&D (Research & Development, Demonstration, and Deployment) continuum, we need the entire private sector working together to get us there.

We’ve done this well as a nation before, in semiconductors. We hit Moore's Law, where we doubled the number of transistors on a chip every two years. One single player couldn’t do it on their own, so Sematech pulled together a commercial roadmap for the entire ecosystem to follow. When you're commercializing hydrogen or LDES, there's so many technologies out there. It's not as straightforward. But that was the inspiration: How do we get an ecosystem catalyzed to all be on the same page? What are the shared assumptions and data that people are thinking about?

Why focus on this now?

Through BIL, IRA and CHIPS, we now have $500B to drive the clean energy transition. This was a natural place for OTT to work closely with the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations (OCED), which has a lot of the money coming out of BIL, as well as the Loan Programs Office (LPO). Because what we want to figure out is how can DOE use its resources to mitigate the risks of climate tech to a point where the private sector feels comfortable to pick up the ball and commercialize? How do we take that $0.5 trillion to activate the $23 trillion in the private sector?

To do that, we need to all get on the same page about what's required. Everyone's excited, but they want to be a fast follower. If we're all fast followers, nothing will happen. I think people are waiting right now, and we really can't wait.

How did you choose these four technologies?

They're all critical to meet our goals for the clean energy transition. You can't meet the energy goals this administration has without nuclear, because it's a steady energy that doesn’t have intermittency issues, like renewable energy does. We need long duration energy storage to support the renewable side of things.

The first few reports are very much aligned with funding opportunity announcements that are being driven out of OCED. There's so much activity right now with hydrogen and the production tax credits that are in place. And then carbon management, which is coming shortly, also has a lot of incentives in place with 45Q. We want to make sure that as this money is going out the door, it’s really helping us understand what the barriers are for the private sector to take over commercial deployment—and where we can buy down the risk as the DOE.

Is there a path ahead you feel most confident about among these technologies? Or one with the most concerning challenges?

So I kind of joke it’s like Pokemon—you gotta catch them all. There's no one single Pokemon that I’m like, ‘Oh, that's the one we have to go get!’ They all are critical. We literally need all of them, and we want to help all the ecosystems succeed as much as we can.

What was the process like for developing these reports ? Who were the key people you spoke with?

In many ways, creating these reports was a way to get the ecosystem aligned—even within DOE. Because, like many big organizations, people are doing different things. And so we were very deliberate to make sure that we had teams that were made of both the R&D side of the house and the D&D side of the house so there’s joint ownership of these things.

A lot of these applied programs have done research in this for decades, and we wanted to make sure we're bringing in the best thinking to that. We also pulled in the National Labs. Then we started looking in the ecosystem to see who's been doing work in this arena, utilizing IEA and other sources, going to conferences and meeting people, to make sure we had the best data and market understanding.

We brought in anybody who wanted to talk to us. Even now there's a [email protected], so if anyone has comments, we want them. We'll be doing road shows and talking about this. In some ways, the work is really starting now, because we put a stake in the sand—here's where we think the pathways are. But we want other people to be feeding into it, and we're going to constantly be updating as we go.

How did this reflect the new role or new approach the DOE is taking? How has the current leadership played a role in that shift?

The DOE has really changed from even when I joined, on day one of the Biden administration. We now have an Undersecretary for Infrastructure—not just for innovation. We now have a big part of DOE that's focused on the demonstration/deployment side, and with dollars through the three laws that we didn't have before. In terms of the RDD&D commercialization continuum, we now have the ability to guide more of that than we did in the past.

The reason why I've been brought here to the DOE is to really understand, how do we bridge that entire continuum? Jigar and David are more focused on the last two Ds, and I'm focused on the entire thing, trying to integrate everything.

The idea is these reports are alive, because—as anyone who's done commercialization knows—what I know now is going to be outdated six months from now. Is it a new way for DOE to do things? Yes, but it's been enabled by a lot of the recent structural changes and new thinking from staff with private sector experience.

How can our readers engage with these reports and with the DOE more broadly?

First of all—read the reports. What we really want them to let us know is, do they agree with the barriers that we've come to? Do these assumptions on cost make sense? Are there other things that they're thinking about? They can tell us by emailing [email protected].

These are not policy reports saying, ‘here's the exact, only one path to get there.’ It's really about what you have to believe, because none of us know the answers right now. We know where the challenges are and what we believe needs to happen from a cost standpoint. But there are a lot of assumptions that will be refined as we start doing demonstration projects. So as people start getting further down the commercialization spectrum, we want them to start giving us real data and input on what they're finding, especially on cost.

These are living, breathing reports. Success here is that the entire ecosystem is owning these reports. This is not a closed system. This is as open as it can be, and we want as many people as possible to be giving us input now.

Are there ways the department can safeguard this work if administrations change?

We have almost two years for this administration, two years to embed this into the private sector—and we are. I've been in the private sector for many years and I've never seen people this excited about the Liftoff and ARL work that we're doing. If the private sector—with its $23 trillion of climate tech investments—buys into this, I feel pretty good that this ARL framework will survive. And it'd be hard to remove, because everyone’s starting to rely on it.

On the ARL side of it, we've been very deliberate on embedding this into DOE and weaving it into our order of operations. This is not a partisan approach to commercialization, this is the way commercialization is done. It’s like in Mandalorian: This is the way. There's no, ‘Republicans do it this way. Democrats do it this way.’ Ultimately, what we're doing is not political. What we're trying to do is get technologies out the door to make the world a better place for the next generations.

Dig into the Pathways to Commercial Liftoff reports and check out the DOE's webinar on the series. Then send your questions, comments, and data to [email protected]!

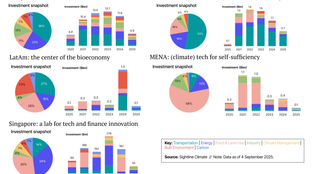

We asked, you answered, and experts weighed in on 2026

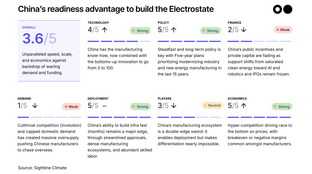

My visit to China's cleantech factories, labs, and HQs

Get the data, insights, and case studies behind the next wave of climate tech