🌍 Your 2026 prediction bets are in

We asked, you answered, and experts weighed in on 2026

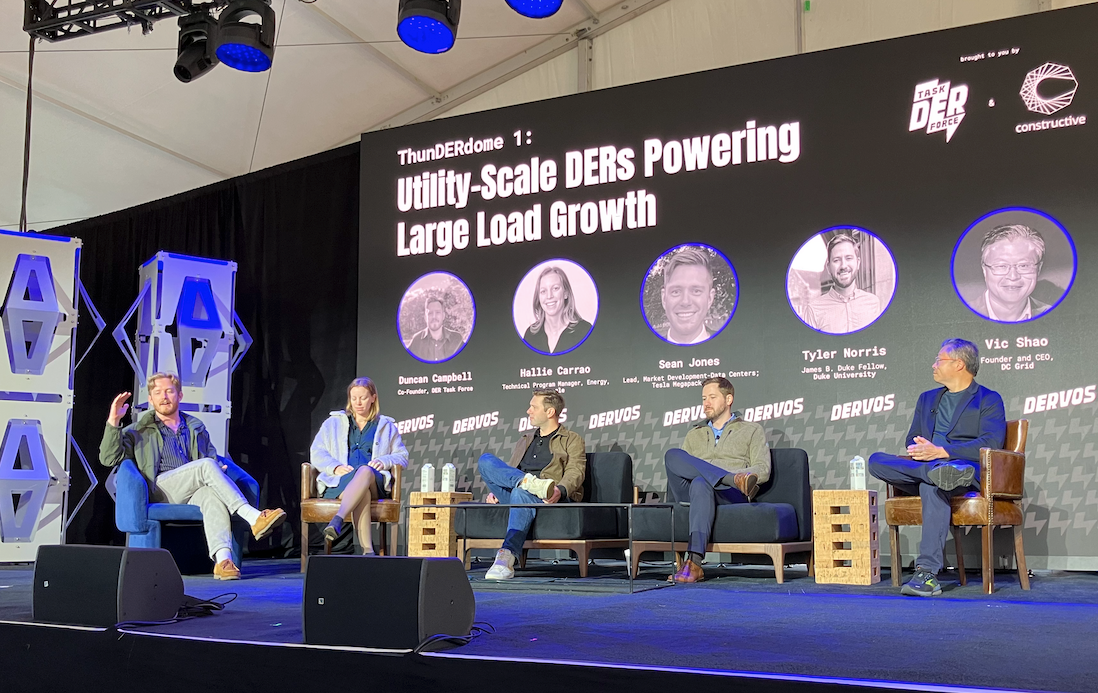

What we heard at the Davos of Distributed Energy Resources

The distributed energy resources (DERs) crowd is one of the wonkiest, most close-knit corners of the climate community. And last week, they had their moment at DERVOS 2025 (the Davos for DERs), which brought together 600+ diehards for a one-day summit, followed by an all-out music fest that kept the party going into the weekend.

Now in its third year, DERVOS took place for the first time on New York’s Governors Island, with attendees ferrying in for a full day of high-voltage debates, the whole thing appropriately powered by portable batteries charged with solar power. DER Task Force, a podcast, newsletter, and Slack community with a high level of organic engagement and an even higher tolerance for hot takes, organized, as usual, with the support of DOE alum-founded convening nonprofit, Constructive. The event gathered investors, builders, corporates, a few utility reps and regulators, and a bevy of self-described energy nerds, all chomping at the bit to geek out over large load tariffs and permissionless balcony solar.

CTVC was there — ferry ride, panels, party and all — and here’s what stood out.

It’s an exciting time to be DER-pilled: For years, DER evangelists have contended that traditional utility planning — adding new generation and new transmission to guarantee firm grid service even at the highest, rarest peak demand — was not the only way to do things. But the case was hard to make because load growth was flat and stubborn soft costs kept DERs from scaling to meaningful aggregate size. Without sufficient incentive, utilities had little urgency in pursuing non-wire alternatives that didn’t fit squarely in their business model.

Now, three things are happening in the market that have changed this narrative:

That means that for the first time in the relatively short lifespan of these technologies, DERs are really, truly hot.

Distributed Energy Resources, according to EIP’s Andy Lubershane, include “any loads, generators, or storage devices interconnected to the electric distribution system or behind customer meters, which can be influenced or managed to help balance supply and demand for electricity on the grid.”

That covers everything from onsite solar and storage to EVs to heat pumps and smart thermostats. A VPP, or virtual power plant, uses software to aggregate DERs into a flexible, dispatchable resource with capacity similar to a mid-size power plant and yet distributed across the grid.

There was palpable excitement as audio from Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome blared from speakers to cue up each ThunDERdome — DER-speak for “panel” — in front of a packed festival-style tent on the Parade Grounds of Governors Island. A non-stop procession of the who’s who in this space took their turn on stage to tear into challenges and solutions, risks and opportunities. Among the highlights:

If a singular theme wove together the event’s many different threads, it was flexibility. Every hyperscaler is prioritizing speed to power (Sam Altman supposedly wants 250GW of compute capacity by 2033 – about a fifth of all US generation currently – for OpenAI alone), while utility-scale renewables are facing headwinds, nuclear needs another decade, and gas turbine supply is already booked out for the next half-decade at least. As a result, any technology or market design or policy framework that can add immediate capacity from the demand side starts to make way more sense.

This isn’t just about DERs.

Flexibility, as a category, includes DERS. But it also covers all the other technologies and regulatory schemes that modify the manner in which electricity is dispatched and consumed across time and space in order to maximize efficiency, reduce cost, and maintain reliability, using the technology we have now. Flexibility is about getting more out of the system without building large-scale infrastructure.

Jigar Shah put the appeal of this category succinctly in the Guardian: Demand flexibility "is one of the few tools that can be deployed at scale over the next few years to eliminate rate increases across the country."

The grid, everyone kept saying, is underutilized, possibly by as much as 40-60%. That’s long been the design: Utilities plan the system for worst-case peaks. Which means, yes, we could 2x the grid with a traditional poles-and-wires buildout to meet the needs of economy-wide electrification and the compute boom. Or we could wring way more value out of the existing grid by changing how we interact with it.

This is Tyler Norris’s bugbear. Default mode in grid planning is for “five nines” uptime. Meaning, the entire system is built to meet a demand so high it only happens about 10 hours a year. That leaves expensive infrastructure laying around for 8,750 hours a year. This fits an old definition of reliability, but certainly doesn’t meet the new standards of affordability and sustainability.

The standard assumption is that data centers — the primary load growth culprit — are inflexible, and that we’ll have to build new generation to accommodate them during system peak. Right away, this doesn't work because generation and transmission buildout is far too slow. Enter flexibility, which can let data centers interconnect to the existing grid. This can work in two ways:

1) The large load becomes flexible

Introducing: quasi-firm transmission. Norris went on Catalyst with Shayle Kann back in March to discuss a study of his that found nearly 100GW of capacity for flexible loads just sitting there, latent in the grid. Here’s how it would work: Allow large load data centers to connect quickly — Speed! To! Power! — with an expedited 90-day study, and then ask, in return, for something like 0.5% curtailment. But this only works if regulators adapt decades-old interconnection processes, and the grid modeling behind them, to provide a clear path for data centers to interconnect faster, if they are willing to be flexible. Few data centers would do it just for brownie points as good grid citizens.

But there’s some traction here. In the Southwest Power Pool, a new regime known as CHILLS grants large loads access to non-firm transmission. This is a prime example of this broader definition of flexibility: It increases utilization of the grid, expedites interconnection, defers costly transmission upgrades, and may ultimately serve as a bridge to firm transmission.

2) The large load pays someone else to become flexible

A more immediate solution might be Voltus’s new “Bring Your Own Capacity” program, which allows hyperscalers to buy capacity from local communities, speeding up the path to interconnection and making them approximately 10% fewer enemies by offsetting potential rate increases. What makes this attractive is that it doesn’t require regulatory reform, it’s not impacted by steel tariffs or other D.C. shenanigans, and it should be straightforward enough to pull off — no construction required.

Or take vehicle-to-grid. As Sunrun’s Head of Grid Services and Electrification, Chris Rauscher, pointed out, the cheapest EV is now cost-equivalent to two stationary residential batteries. An F150 Lightning is equivalent, from a storage capacity perspective, to ten Tesla Powerwalls. If California can figure out how to tap into those resources and get power flowing back to the grid, it could tap into grid-scale amounts of distributed storage. That would also help customers subsidize their EV purchase by increasing utilization of those moving, honking batteries.

The takeaway from this conference is that there’s a vibe shift underway in clean energy — a new tip of the spear. In no small part due to federal headwinds, the locus of greatest activity and excitement has migrated from plugging in as many utility-scale renewables as possible (which we still need to do) to building out DERs, aggregating them into VPPs, and finding flexibility everywhere it’s hiding. This is true at least from a momentum-tracking perspective, if not yet from a GWh perspective.

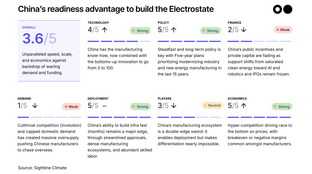

Jesse Peltan on the DER Task Force podcast: “People do not appreciate the difference in scale. China’s targets for their solar and battery manufacturing capacity — 2TW of solar and 8TWh of storage — that’s an entire US worth of electricity generation. That’s like 4,000TWh of 24/7 solar power. They’re going to be able to make that every single year by 2030.”

Ian Magruder: "There’s a growing recognition that our electric grid is underutilized and by increasing utilization (squeezing more out of the system we have through batteries, demand response, etc.) we can both meet the increasing demand for electricity and save Americans billions of dollars."

James McGinniss: "People don’t care about VPPs, they care about cold beer and warm showers.”

Chris Raucher: “There’s nothing virtual about them. They’re distributed f***ing power plants.”

Duncan Campbell: “Feels like the end game is batteries everywhere.”

Tyler Norris: “On the five nines uptime requirement… if you try to plan for always, it’s hard to have that not lead to thermal solution.”

Corey Ramsden: “Small-scale, customer-facing, productized, permissionless DERs will be a forcing mechanism like rooftop solar but on steroids due to potential speed of adoption, forcing utilities and commissions to get their shit together even faster to get value from DERs.”

Miles Farmer: “To enable large load customers to provide flexibility on capacity, we need ways to reward them in the load interconnection process for being flexible.”

Jigar Shah: “Electricity bills are too damn high.”

Dana Guernsey: “The idea that utility meters are more accurate than other sources is just not true.”

Tyler Norris: “Why don’t we have quasi-firm transmission tiers? Load-serving entities don’t want it because it challenges their business model.”

Allison Bates Wannop: “Community doesn’t have an easily quantifiable payback, or a straight line ROI. But communities take care of each other. Communities solve problems.”

James McGinniss: “Flexibility is dope.”

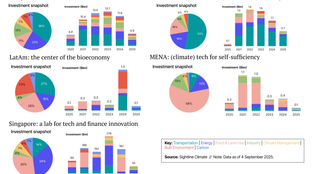

CTVC is powered by Sightline, the tactical market intelligence platform for energy and investment decision-makers.

Thanks for reading! Not a subscriber yet?

We asked, you answered, and experts weighed in on 2026

My visit to China's cleantech factories, labs, and HQs

Get the data, insights, and case studies behind the next wave of climate tech