🌍 Your 2026 prediction bets are in

We asked, you answered, and experts weighed in on 2026

There’s a famous Chinese proverb, “hide your strength, bide your time” (韬光养晦, tāo guāng yǎng huì), that encapsulates China’s stealth-ish rise to utter dominance over the world’s clean energy supply chains. The West is now finally confronting the consequences, but it may be too late.

We know the history lessons of Cleantech 1.0 all too well: the West innovated technologies like solar PV, only to be outmaneuvered by China. This time, as we near yet another peak-to-trough moment in Climate Tech 2.0 (3.0?), the same concerns loom large: Can the West really rebuild its manufacturing base and bring back production in solar, batteries, and EVs, or has that ship sailed? What happens to the next wave of emerging climate tech — hydrogen, SAFs, nuclear, carbon capture, fusion — will history repeat?

Today, the backdrop is completely different. As the world marches toward electrification, with clean energy generation meeting most of the surge in global power demand, China now manufactures 80% of the world’s solar panels, 60% of the planet’s wind turbines, 70% of its EVs, and 75% of batteries. The US and Europe have responded with antiquated tariffs and trade barriers, trying to trip up China’s manufacturing machine. Inside China, years of overproductive manufacturing combined with Western trade restrictions have led to a cycle of involution (or “neijuan” 内卷 which literally means curling inwards): cutthroat internal competition slicing into Chinese suppliers’ profits. At the same time, the US has reversed course from the historic $370bn Inflation Reduction Act to a full-fledged climate retreat under Trump 2.0. At COP this year, China’s pavilion drew crowds, while the US was noticeably absent.

To really understand what’s happening, I went to see it myself. After visiting China’s factories, labs, and OEM headquarters, and speaking with engineers, investors, and policymakers, I’m kicking off a new series to share what I learned.

You may have read other reports on China’s energy transition, brimming with eye-popping market shares and hockey stick growth. This isn’t going to be like that. Instead, I want to go behind the scenes to the heart of what’s driving China’s leadership in cleantech. In this first edition, we’ll cover:

But this is just the beginning of our China coverage. There’s more to unpack than could ever fit in a single newsletter. In an upcoming series on Sightline, we’ll go deeper into China’s top-down and bottom-up industrial policy, the secret to its manufacturing ecosystem success (convergence = compounding), the state of public-private investment, competition and IP protections, sector deep dives, case studies on the leading companies (BYD, CATL, etc), and implications for the future of energy. We’ll answer questions, like:

As a long-time climate tech analyst with an ethnic Chinese background, I’ve always felt a quiet insecurity about my China-sized blind spot. My parents came to the US, from China and Taiwan, when they were in grad school. Growing up, on visits, I watched China transform itself every few years, from smog-choked streets to an almost too-perfect utopia of spotless cities, high-speed rails, EVs, and seamless payments.

Last month, I went back to China with a group of US and European founders and investors on a mission: to unpack the secrets behind China’s cleantech success, and what lessons companies and investors can learn from its rise. It was hosted by Persimmon Systems, a global manufacturing consultancy helping Western innovators access Chinese supply chains. Over five days, we traveled across seven cities, visited ten company HQs and three factories (battery, solar, and perovskite), and rode four high-speed rails. From factory floors to boardrooms, we met giants like BYD, CATL, and GCL, as well as emerging players like Solidlight (semi-solid batteries), GCL Perovskite (tandem cells), Windrose (heavy-duty EV trucks), and Hydotech (electrolyzers).

I arrived at an opportune moment. China had just released the draft of its 15th Five-Year Plan, the roadmap for its industrial priorities from 2026 to 2030. These plans have underpinned China’s rise from post-Cultural Revolution doldrums to manufacturing superpower status (more on this in a later edition). And while I was there, Xi and Trump met in South Korea to hash out a deal to temporarily lay down both sides’ weapons, one on tariffs and the other on access to rare earths. It was a brief geopolitical pause and a window into China’s energy future.

China is driven by energy security first, and global industrial leadership second, not decarbonization (the New Joule Order applied). While the West leads with climate as its rationale for building clean energy industries, China treats it as a strategic necessity: a way to reduce dependence on foreign energy and position itself as the dominant power in the next energy era.

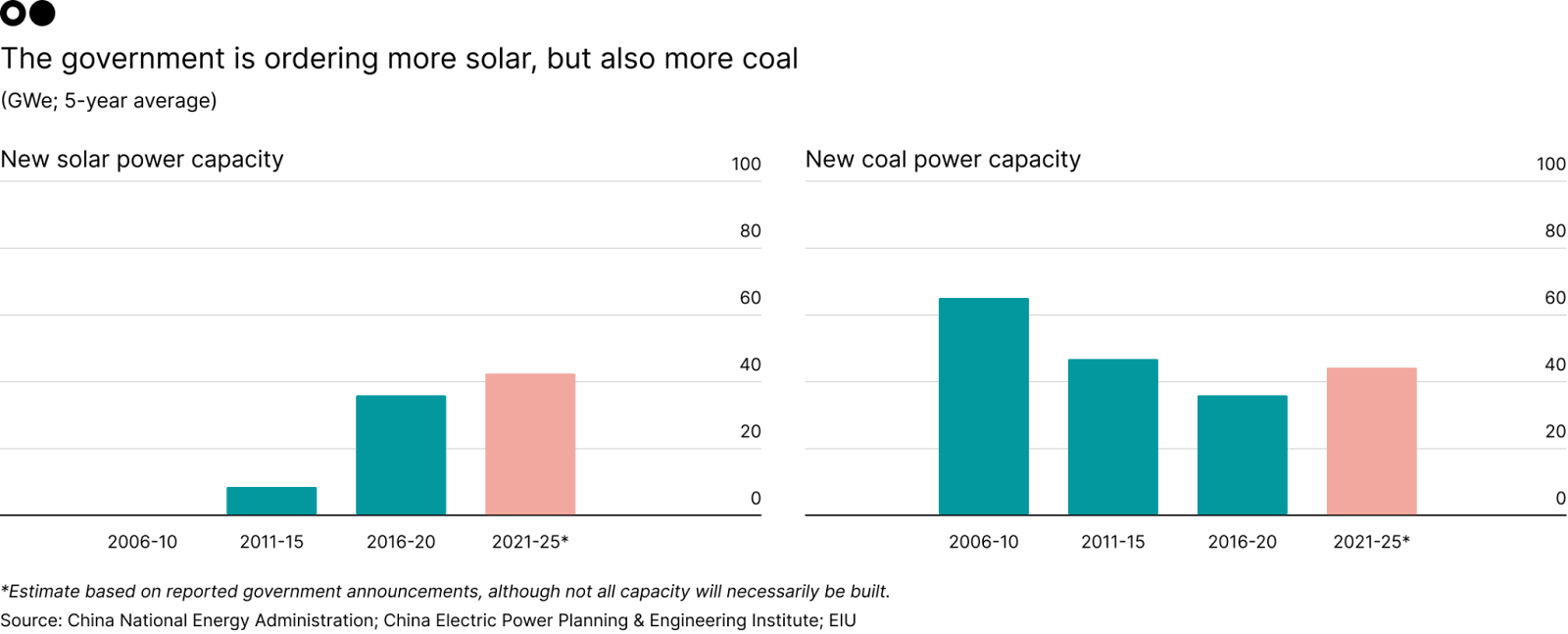

A second principle, “establish first, then break” (先立后破), defines China’s modern energy strategy. After aggressive renewable buildout contributed to rolling blackouts in 2021, Beijing reframed its approach: secure baseload first (coal, nuclear, hydro) then phase out fossil fuels once stability is guaranteed. This is why China accounted for 93% of new global coal-power construction in 2024. It prefers burning its own coal over relying on Middle Eastern oil or US LNG. In other words, it's Energy Addition first, then Energy Transition.

China also views “new energy” (新能源) as a form of soft power. With the US retreating from climate leadership, China sees an opening to shape the next global energy order. Its strategy of 弯道超车 (“overtaking on a curve”) is about leapfrogging traditional players by rewriting the rules of the game. In EVs, China understood early it couldn’t win on combustion engines, so it opened a new track in electrification, where domestic companies could lead, changing the competition itself.

Underlying all of this is a rooted belief that the fossil fuel economy has run its course, and the electrostate — a society run on clean and reliable electricity — will take its place. And this belief isn’t limited to policymakers or executives. Anyone I spoke to, from Didi drivers to family friends, knew more about “new energy” than your average American.

It fits into the thesis from Dan Wang’s recent book Breakneck (highly recommend) which offers a useful lens for understanding the China-US divide: China is an engineering state, bringing a sledgehammer to physical and industrial problems, while America is a lawyerly society, bringing a gavel to slow, reshape, or litigate almost everything. You see the split in institutions: China’s Politburo is filled with former engineers, while the US Congress is dominated by lawyers, not to mention in how each approaches industrial scale.

In the West, the US and Europe saw an incredible run-up of private capital interest in the early 2020s, with almost $112bn of climate tech venture capital from 2020-22. But most of these early-stage solutions soon got stuck in the infamous “Valley of Death” that also befell Cleantech 1.0 cos. Well-meaning industrial policies like the IRA aimed to fix this, but became mired in rulemaking, guidance rounds, and tax-credit eligibility debates. Few technologies have fully benefited from the IRA, e.g. almost no hydrogen projects have secured the 45V credit, because policymaking has been slow, contested, and procedurally complex. And this “lawyerly” behavior reflects in our endless debates on defining the “missing middle,” “FOAK,” or “scale gap” challenges. I once joked we spend more time debating these definitions than actually getting stuff done. The West’s constant and unnecessary rulemaking can, and often does, get in the way of building things.

China, by contrast, has the opposite problem: engineers build so quickly and relentlessly that the system often overshoots, triggering involution where hyper-competition collapses margins. Decades of “building mode,” coupled with ~4 million STEM graduates a year (the US has ~800K), have produced unmatched manufacturing muscle. Top-down policy paired with aggressive local-government incentives generates a kind of industrial tournament: provinces compete to win and scale strategic sectors. The 14th Five-Year Plan’s push for new energy vehicles created an explosion of 130+ EV brands with prices driven below $8,000 and entrants ranging from provincial champions to smartphone makers like Xiaomi.

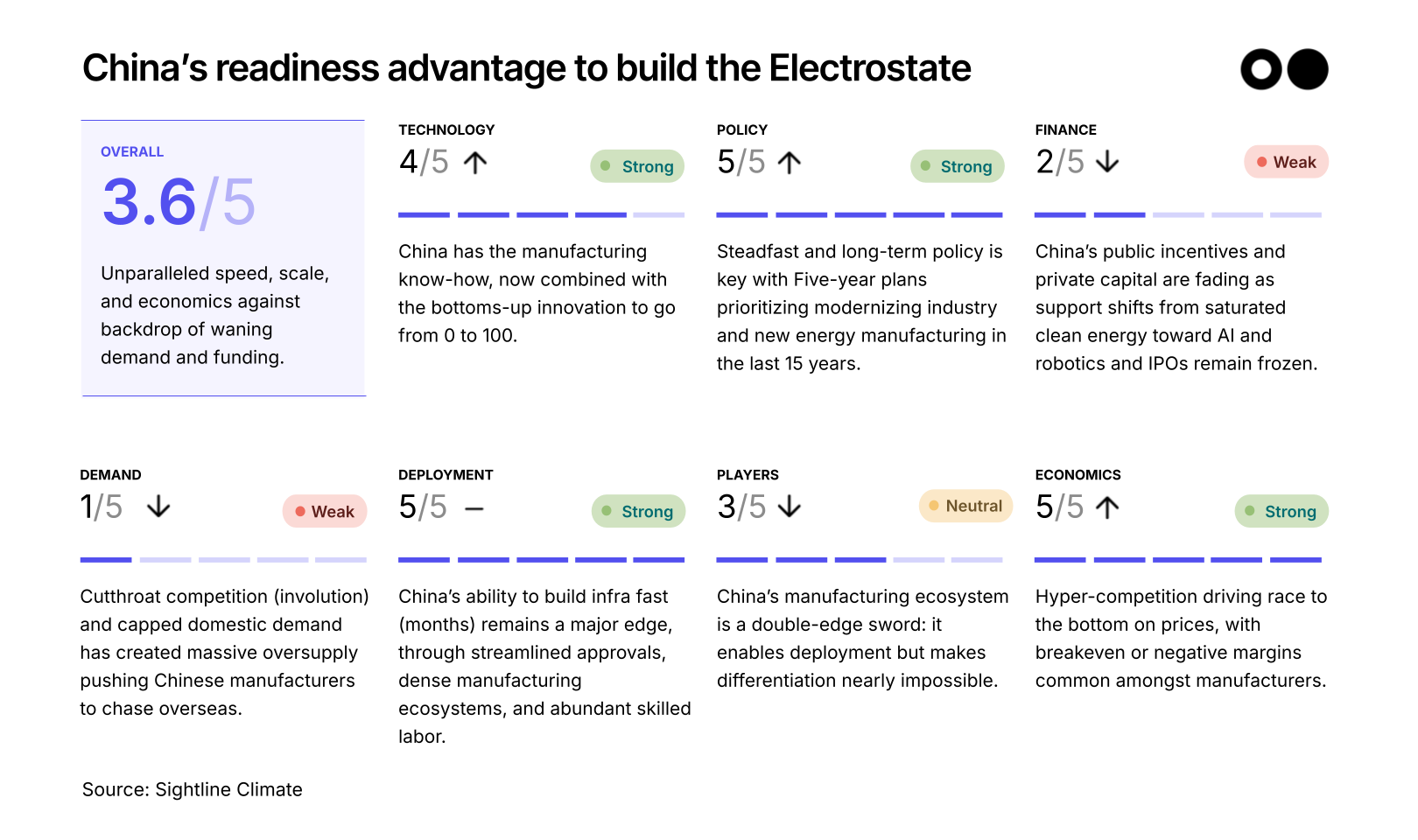

If we look at China through the lens of the Sightline readiness curve (our proprietary methodology for evaluating energy market readiness), it also becomes quite clear how China has become the world leader in manufacturing.

Strong, getting stronger. The perception has been that innovation first happens in the West, then scales in the East. But with Dan Wang’s definition of technology, technology isn’t just “innovation” but rather the communities of engineering practice and manufacturing process knowledge. When Shanghai welcomed Tesla’s Gigafactory in 2018, the government deliberately invoked the “Catfish Effect” (鲶鱼效应 nián yú xiào yìng), or putting a “catfish” in the fishtank; whichever companies survived would become the strongest globally. It worked, catalyzing a boom in EV talent and process innovation, with BYD emerging as the strongest fish in the tank.

Strong. China operates like a company more than anything else: Xi as “CEO,” the Politburo as the exec team, setting top-down goals every five years, with local governments executing and being judged on performance. (Those who do well move up the political apparatus, like division managers.) This centralized direction paired with decentralized implementation creates the hyper-competitive environment that drives China’s build-at-scale culture. And similar to the US, China embraces supply-side policy vs. demand-side (like Europe). It uses local government funds and incentives like favorable zoning laws to build factories. China's ETS is currently pretty weak at $10/tCO2 vs. Europe's $80/tCO2.

But I can't emphasize enough: China's mandate to build clean energy industries has been primarily driven by energy security and economic leadership, not decarbonization.

Strong, getting weaker. China is an example of public-private partnerships done well. Local governments align with national (five-year plan) priorities and set up industry funds with state-owned or private partners. They collaboratively help companies secure sites, fast-track permits, finance part of the capex, and even build factories that are later leased back to operators at negotiated rates. Startups can raise VC, but the bar for traction is higher than in the West. State-owned enterprises also benefit from much lower-cost bank capital, though many leading cleantech champions are privately owned. Recently, however, incentives have faced belt-tightening as budgets shrink and strategic focus shifts from saturated cleantech sectors toward AI and robotics to compete with the US.

Weak. Intense hyper-competition has created an oversupply, especially in commoditized sectors like solar PV. GCL told us there’s roughly 1 TW of supply for ~600 GW of demand. With domestic demand saturated and US markets cut off by tariffs, suppliers are pushing into Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. Europe and the U.S. still offer the highest price premiums; Africa is growing but low-margin; and India’s ALMM list makes market entry difficult.

Strong. China has mastered deployment speed and scale. Building a new factory takes 6-8 months in China, versus 2-3 years in Europe and 3-4 in the US. The difference comes down to regulation, cost, labor flexibility, and local government incentives. Officials are rewarded for clearing the way for manufacturing projects, supply-chain equipment is cheap and nearby (often within just a few miles), and skilled technicians are abundant. Even universities pilot hardware at scales comparable to (or larger than) VC-backed startups in the West.

Neutral. This is a double-edged sword at its sharpest. On one hand, Chinese manufacturing ecosystems are so robust that you can convene a meeting with all of your relevant suppliers in one room the next morning, especially in industrial manufacturing hubs around Shenzhen or Shanghai. This is by far China's decisive advantage, but also the downfall of many players. Since the barriers to entry are so low, almost anyone can get in the game especially in commoditized sectors. There is almost no lasting competitive advantage in China, besides scale and resilience. One of the reasons why solar modules became commoditized, so fast, is the extreme speed of information dissemination through the supply chain, i.e. equipment suppliers may inadvertently mention process details to competitors in sales conversations. IP protection can't stop gossip.

Strong. Hyper-competition is driving a race to the bottom on price, where breakeven or negative margins are the norm. Solar module makers told us there’s virtually no cost-down left, with manufacturing efficiency already optimized to the bone, down to trimming panels from 210mm to 182mm just to maximize shipping-container density. The only frontier left is performance, which explains the surge of interest in next-gen tech like perovskites. The same dynamics play out in batteries: Chinese producers willingly give discounts north of 40% to offset the US’ 30% ITC gap.

Thank you: I want to give a massive thank you to Sharon and Roger from Persimmon Systems, a global manufacturing consultancy helping Western innovators access Chinese supply chains, for giving me this window into China.

Not a CTVC subscriber yet?

We asked, you answered, and experts weighed in on 2026

Get the data, insights, and case studies behind the next wave of climate tech

What we heard at the Davos of Distributed Energy Resources