🌍 Getting current on kelp processing with Macro Oceans

The synthetic bio startup sees an upswell of seaweed applications beyond the food industry

How can we sustainably replace a $150B total addressable fertilizer market that is critical to global food supply?

Back in the 1910’s, two German scientists named Haber and Bosch developed a process to manufacture ammonia. As a result, they fed the world, fueled modern explosive warfare, and won two Nobel prizes for creating a fertilizer that was cheap, plentiful, and effective (and coincidentally replaced the previous best alternative, batshit). Today, we still produce nitrogen fertilizers like ammonia in city-size factories powered by fossil fuels that contribute some 2% of total global greenhouse emissions. 60% of fertilizers don’t make it to the plant, running off into waterways, producing algal blooms, and poisoning drinking water – unless first volatilized into noxious gases.

How can we sustainably replace a $150B total addressable fertilizer market that is critical to global food supply? Nitrogen is a building block of life and all plants require it to grow – the precarious economics of Big Ag make fossil fueled fertilizers a necessity for scale, and organic alternatives (e.g. manure, fishmeal, compost) are expensive, prohibitively local, and pathogenic. For a solution to work, we must be able to produce more food than we have been able to produce before (as world population growth increases) while also replacing the energy equation that otherwise perpetuates an oil addiction undergirding our food.

There’s three primary approaches to reshaping this dynamic: 1) more effective fossil-fuel based fertilizers (e.g. clean synthetic ammonia), 2) improved application (e.g. more effective uptake and controls to reduce runoff) and 3) nutrient-light agriculture (e.g. less corn, more legumes). Across these approaches, the common thread is that the paradigm of synthetic fertilizers reigns supreme – there is no ready substitute, only slightly less bad options.

Today, only some 5% of total agricultural production costs for individual farmers are fertilizers yet these represent a lion’s share of all greenhouse gas emissions caused by farming. This is a negative externality globally, though individually (unfortunately) a minor concern for those directly deciding which fertilizers to grow with and whose options have previously been pretty limited.

However, there are a handful of contenders that are looking at the equation of fertilizer to food output with fresh perspective, trying to both invert the equation while acknowledging Haber and Bosch’s self-evident triumph of man over soil:

The broader context remains that farmers are fundamentally risk-averse. Consumers mostly disregard their food’s production process for price, convenience, and selection. Carbon pricing may change the fundamental unit economics, which would increase organic fertilizers’ ability to stay par (if not compete) with current structures. Accounting for nutrient run-off (e.g. such as in California) would also tax the less-efficient approaches by penalizing situations where effectiveness is mismatched vs. volume. Ultimately, the drive towards a highly potent (effective), low run-off solution would open up an opportunity for existing agricultural interests to retain their edge while creating fertile ground (ha!) for more new innovations.

Editor’s note – I retain equity in and remain an advisor to Kula Bio, but sharing the above overview given all the dynamism (and my excitement for!) the space.

Interested in more content like this? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter on Climate Tech below!

The synthetic bio startup sees an upswell of seaweed applications beyond the food industry

A gut check on reducing bovine burps

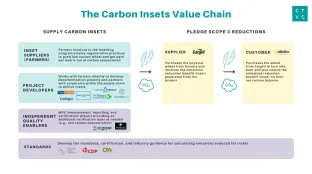

The underappreciated role of carbon insets in decarbonizing Scope 3 supply chains