Rhodium: Taking stock of Paris targets

Late breaking ‘Inflation Reduction Act’ changes odds for the better w/ Rhodium’s Ben King

This week, we chatted with Varun Sivaram – a physicist and clean energy expert.

This week, we chatted with Varun Sivaram – a physicist and clean energy expert. He is currently a senior research scholar at the Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University and was formerly Chief Technology Officer of ReNew Power – India’s largest renewable energy firm.

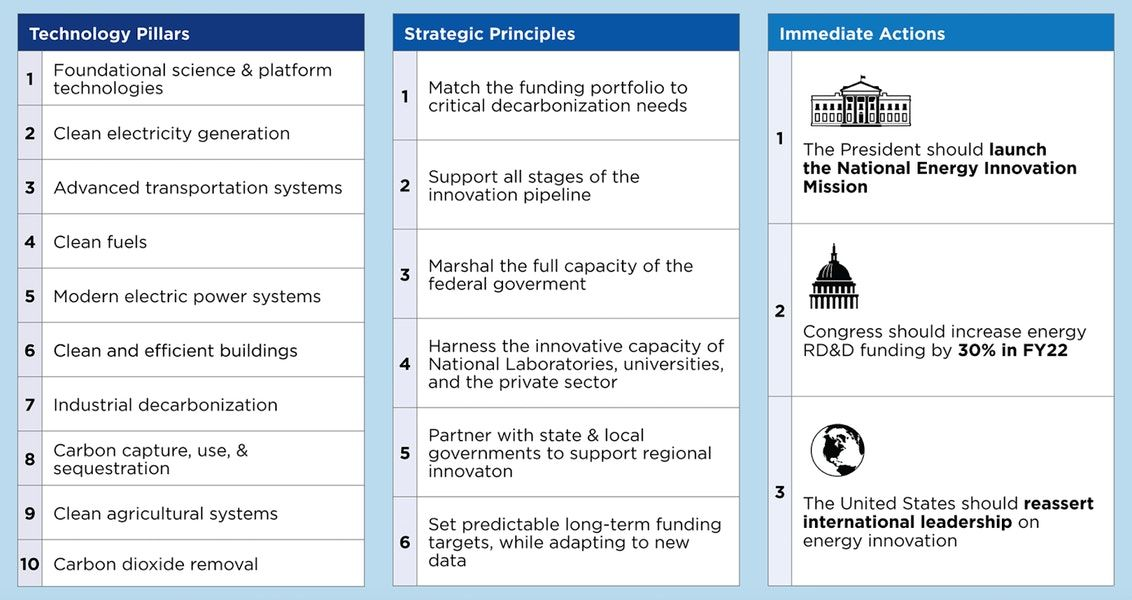

In September, Varun and co-authors strategically published “Energizing America: A Roadmap to Launch a National Energy Innovation Mission.” The authors propose launching a National Energy Innovation Mission and ramping up clean energy innovation spending to $25 billion annually by 2025. According to Bloomberg, “the book details down to the budget line item exactly how much money America should spend and how it should spend it”:

Can you talk a little about your past experience and what drove you to put together this report?

I’m committed to advancing clean energy innovation to achieve decarbonization, and I’ve spent my career working across multiple sectors. I started in academia researching perovskite solar cells, worked in government and policy research, and invested in innovation in the private sector. So the through line for me, across all these different sectors, is innovation. Within every one of these sectors, innovation is necessary to achieve the energy transition and transformation we need. Energy, in particular, suffers from a market failure because of underinvestment in innovation.

Now, we have a bipartisan majority in Congress that’s increasingly supportive of energy innovation and a potential administration that’s put innovation at the center of its climate and energy plan. We wrote Energizing America because we started to see more interest in clean energy R&D funding, but there was no roadmap to achieve the high-level spending targets. We wanted to establish a coherent strategic vision and give a detailed line-by-line action plan ahead of a potential transition. Over the last year, the team and I—spurred on by Jason Bordoff—got to work and put together this book.

How did you approach building the budget lines to your roadmap?

We looked through hundreds of government reports to try and deduce which funding programs could be classified within clean energy innovation. Then we did a bunch of work triangulating the priority initiatives to support the priority technology areas. We tried to be thoughtful about which dozens of initiatives should be funded across these 10 technology pillars. And at a high level, we think $25 billion strikes the right balance between getting to that scale and not ramping up too quickly (i.e., where you might misspend taxpayer dollars).

What was the rationale behind the recommendation to create a National Energy Innovation Mission?

Today, clean energy R&D is too little and, frankly, too concentrated within the Department of Energy (DoE). The defense and health innovation missions over the last half century have demonstrated that a certain scale of funding – a whole of government approach – and durable political consensus are necessary for these innovation missions to really succeed in a long-term, sustainable way. So, we proposed a scale of funding at ~0.1% of GDP (which is still lower than health innovation funding) that will get us to the order of magnitude needed to create self-sustaining ecosystems – where universities and companies start to dedicate programs to innovation and know there will be sustained support and demand for their technologies.

In the health sector, this model has worked very well. For example, the National Institutes of Health has successfully supported all 210 of the FDA-approved drugs from 2010-2016. We want to replicate some of that success, but in our own unique way, for energy.

The durable political consensus is also important. Principle five in the roadmap is to spread funding across communities all over the country to cultivate these innovation clusters and build that durable political consensus that will outlast this next administration. It’s going to be critical that this National Energy Innovation Mission outlasts any administration and that the US commits to energy innovation the same way it has committed to defense and health. We’ve done this in the past. Now let’s do it again for energy.

What are the current governmental organizations for funding energy R&D? How are they set up, and how much power do they have?

Government funding is actually not that diversified. When the Obama Administration spearheaded the Mission Innovation commitment for countries to double their R&D funding for energy by 2021, they had to do detailed accounting of clean energy innovation government funding. They found that most of the money went through the DoE, but over a dozen other federal agencies supported clean energy innovation such as the Department of Defense (DoD), NASA, and NSF (which all had far smaller chunks of money than the DMV). Today, we don’t have a database since the Trump administration failed to double funding and stopped measuring it.

So our first task in this research project was to create the most comprehensive database that exists. Fortunately, my co-authors Colin Cunliff, David Hart, Julio Friedmann, and David Sandalow are very knowledgeable about federal government budgets for energy. After we created this database, we saw the potential for ramping up clean energy funding for agencies like NASA or NSF, which have tremendous R&D programs. These agencies have complementary approaches, with some focusing on earlier-stage innovating in national laboratories and others focusing on the later-stage testing and validation, and working with the private sector. Each of these agencies also have their own missions. The DoD wants microgrids for their bases, whereas NASA is working on lightweight solar cells for satellites. When you put them all together, you get a diverse range of energy technology priorities and ways that these agencies operate.

Today, 75-80% of funding goes to the DoE. We propose that by 2025, after we’ve tripled funding to $25 billion, roughly half will go through the DoE and the other half to other agencies to ramp up innovation faster.

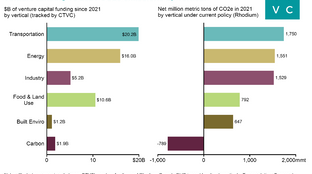

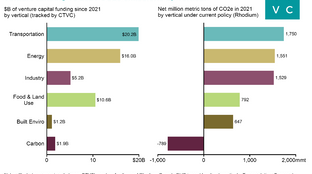

In the report, you show the disconnect between the sectors in the U.S. responsible for emissions and the corresponding research budget through the Department of Energy. Why do you think we’ve misallocated funding in the past?

The way that the federal government has been set up to support energy innovation was not with the explicit purpose of decarbonization, so this misallocation is not surprising at all. In the 1970s, the Department of Energy was created by consolidating a bunch of agencies and was structured with fuel and technology groups separate – rather than a holistic approach. Over time, that path dependence has led us to focus on funding technologies disproportionately. We support electricity innovation with half of our R&D dollars, despite it being less than half the source of emissions. Industry, transportation, or agriculture all contribute disproportionate emissions compared with the amount of funding dedicated to them. So we set out very intentionally to dedicate the largest proportional funding increases to the technology pillars under resourced today.

To remedy this mismatch, you suggest tripling the money for carbon capture and storage (CCS) from $115 million a year to $300 million. Why CCS?

Two weeks ago, the IEA came out with a report which emphasized that it’ll be impossible to achieve a net zero energy transition without CCS. And yet, CCS lags significantly in its level of maturity and deployment. This report, along with Julio’s recent Net-Zero report, gives some room for optimism since the US has the largest number of CCS pilot and demonstration facilities in the world. However, far more demonstration facilities and advancements in technology are needed. I’m a solid state physicist by background, and I would love to see advanced materials making carbon capture cheaper and more efficient.

How should we balance between focusing on innovation and deployment?

The IEA came out with another extraordinarily impactful report a few days before Energizing America. Their report emphasized that half of emissions reductions for a swift net-zero transition must come from deployment and the other half from technologies that haven’t reached commercial markets yet. Mature technologies like solar and wind will be enabled by a host of other innovative technologies that have not reached the market yet. For example, one can combine renewables and hydrogen to better decarbonize industry

Unfortunately, according to the IEA, 40 out of the 46 clean energy technologies are not on track. Given this, clean energy innovation should be the centerpiece of a clean energy and climate plan. That’s why I’m thrilled Vice President Biden has made it the centerpiece by calling for the “largest ever investment in clean energy research and innovation.”

Within these sectors, what technologies are you personally most excited about?

I advise three different companies I’m really excited about. One is working on large wind turbines, another on floating solar, and the last on orchestrating a smarter electricity distribution grid. This maps to my passion for advanced renewables and digital technologies that enable clean energy systems. My first book called Taming the Sun, was all about solar, and I did my PhD on perovskite solar technology. The opportunity to have lightweight, low cost, flexible, semi-transparent, solar PV that is more efficient than what we have today in silicon could revolutionize solar and make it easier to use solar for new things like the production of green hydrogen or the desalination of water.

My second book Digital Decarbonization covered the potential of digital technologies. When I was at ReNew in India, we created a digital laboratory, which improved our ability to forecast solar and wind production, forecast load for our customers, and predictively maintain our wind turbines. One of the companies I advise, Camus Energy, has a wonderful toolkit honed from large distributed computing systems from the tech giants to make distribution grids more resilient, flexible, and adaptive. I think these digital technologies are critical and a place where the US and India can lead.

The big elephant in the room is the election coming up. Despite the fact that climate should be a bipartisan issue, to what extent will your roadmap’s implementation be contingent upon a Biden administration?

I am fairly confident that there is strong bipartisan support for clean energy innovation funding in Congress. We’ve already seen budgets rise in clean energy R&D despite the Trump administration trying to slash them every single year. This is one of the few areas where Republicans have been willing to display resistance to Trump. Still, I think it’s going to be critical to have a Biden administration to orchestrate this whole ramp up, which isn’t going to be easy. You have to orchestrate a few dozen federal agencies, harness their complementary approaches, and make sure that you’re funding different research performers. Getting the full effect of a National Energy Innovation Mission will require a Biden Administration in office. I’m fairly certain that he’s going to win, but we have a lot of work ahead of us.

In terms of the report itself, we’ve gotten wonderful reception from folks on both sides of the aisle. Democratic staffers from the committees which appropriate money have reached out to us asking for our spreadsheets. Kathy Castor, a Democratwho leads the House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis, which put out their own report, has also been amazingly supportive. If I leave you with anything, it’s that R&D innovation is not polarizing. It’s a Goldilocks situation where folks don’t realize that innovation is the one thing we can count on to be an ambitious and realistic climate policy, so we should be going full steam ahead on it.

Interested in more content like this? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter on Climate Tech below!

Late breaking ‘Inflation Reduction Act’ changes odds for the better w/ Rhodium’s Ben King

Out in front on carbon removal, Nan Ransohoff sets a new tier for climate leadership with Frontier

John Doerr and Ryan Panchadsaram's new book on OKRs to get to Net Zero